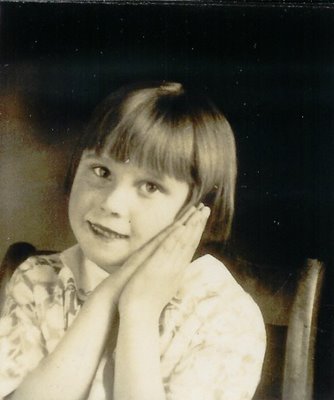

LITTLE ORVALETTE

AGE 8 (approx.)

PENNY ARCADE PHOTOS TAKEN AROUND 1929

"I won't actually hit you. I promise." This was roughly what her older brother Paul said to little Orvalette when he was trying to coax her that first time into putting on boxing gloves and sparring with him in the attic of their Illinois home. I can see her reluctantly trailing behind brother Paul up the steps to the dimly lit attic with its musty smells and collection of cobwebs that swayed in the draft.

Paul didn't mean to hurt her. He had good intentions. He would not have hurt her on purpose. But with all that weaving from side to side and dancing about like a pro, he must have gotten caught up in the moment, because he bopped her on either the chin or the nose and, with that, their first sparring match ended abruptly. Unfortunately, Orvalette was gullible and trusting. So, a few more sparring matches followed with always the same empty promise made beforehand "I promise this time. I won't hit you....". Finally, after receiving enough unintentional jabs from the left and from the right, she learned her lesson. She learned that you can't believe everything your brother tells you even when you want to. Orvalette gave up boxing for good.

The youngest of seven children, Orvalette was born in 1922 in the hills of Kentucky. She started out in life as a hillbilly. As an adult, she used to joke about being a hillbilly, but at the same time she was embarrassed by it. Her parents were hill people. They knew folklore and folk songs and folk remedies. Her mother was married by age 14. Both her parents were uneducated having gone no further than the third grade. Yet, they managed to acquire the life skills they needed to make a living and get along.

When she was a baby, Orvalette nearly died. She contracted an intestinal disorder that threatened her life. The only nourishment she would accept was buttermilk. The doctor and everyone else warned her mother that the buttermilk would make the child's condition worse. In spite of the warnings, her mother fed Orvalette the buttermilk anyway. She decided that if the child was doomed to die it would not be on an empty stomach. Orvalette did not die. She recovered. Was it the buttermilk that was responsible for Orvalette's miraculous recovery, or was it the magic of her mother's nurturing? I lean toward the latter.

Living was hard for Orvalette's family in the hills of Kentucky in those times. Laundry day for Orvalette's mother involved hauling water up from the creek, which was some distance from their house, and heating the water in a big kettle over a fire built outside in the yard. In spite of hardships like this one, her mother was a clean woman who was so meticulous about it that she would sweep away the dust that accumulated on the bare, hard clay soil in that yard.

Switchings were the preferred method of disciplining a naughty child back then in the hills of Kentucky. Orvalette was no exception. When she was naughty, which is hard to believe she ever was, her mother would send Orvalette outside to find a switch. She would return with the smallest switch she could possibly find only to be sent back outside to look for one that was sturdy. In those days, switchings were considered necessary and part of being a good parent.

Orvalette's family moved from Kentucky to northern Illinois when she was about six years old. Shortly after they moved to Illinois, she was playing outside in their front yard when a Catholic priest walked by. He stopped to chat with her. As the story goes, he asked her "Are you Catholic?" Orvalette replied, "No, I'm English American." Apparently she had never been exposed to Catholics and did not know the meaning of the word. Later on in life, she fell in love with a Catholic, married him, and became a Catholic herself.

As a child, Orvalette liked to comb her father's hair. She would stand behind him while he sat in a chair and she would comb his hair and sing to him. She sang That Silver Haired Daddy of Mine. Gene Autry wrote that song. It was popular during the early 1930's. Orvalette would have been nine or ten at the time.

Orvalette's father had a pet name for her. He called her Dinktum which is from the folk song Teedle Dinktum Dinktum Day. He also had the annoying habit of flicking her on the head with his index finger. He thought he was being affectionate, but she thought it hurt.

We take for granted the abundance of food that exists today. It is not uncommon today to allow the last few oranges in the fruit bowl to shrivel up, or to neglect those last few oranges in the refrigerator bin until they grow moldy. But when Orvalette was a child, an orange was something children might discover to their delight in their stocking on Christmas morning.

Since her mother was from the hills of Kentucky, Orvalette probably ate plenty of beans and cornbread as a child. In addition to that, she probably feasted on biscuits and gravy, bacon and eggs, black-eyed peas, and wilted greens. But her mother's signature dish, which she would have prepared on Sunday for the family, was chicken and dumplings.

Sugar was inexpensive during the Depression years while Orvalette was growing up. So to satisfy everyone's sweet tooth in the family, Orvalette's mother would have made plenty of fruit cobblers. She would have used the fruit she canned herself. She would have brought the sugared fruit to a low boil and dropped dumpling strips into it. That was her version of fruit cobbler.

The radio entertained families at home when Orvalette was a child. She would have had her ears glued to the radio back then and she would have listened to such popular radio shows as Amos and Andy, Fibber McGee and Molly, George Burns and Gracy Allen, The Lone Ranger, The Green Hornet, and The Shadow. Fibber McGee's trademark was his closet which was packed with everything under the sun. Each time the closet door was opened during the program then, the radio audience could hear the clatter of things falling helter-skelter out of the closet onto the floor. It must have enlivened the imagination of a child. The expression "Fibber McGee's closet" became popular. As an adult Orvalette used that expression when describing a closet that might be in that much disarray.

Orvalette would have gone to the movie theater as a child during the Twenties and seen silent movies featuring such greats as Charlie Chaplin. Once sound arrived, she would have seen It Happened One Night with Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable which came out in 1934.

By the time Orvalette was twelve years old, she knew how to drive a car. At that age she was chauffeuring her parents around who never did learn how to drive a car.

Once she became a teenager, Orvalette did what other teenagers did during the Thirties. Since money was an issue back then, a date might be nothing more than the boy and girl going to the drug store in town, sitting at the soda fountain there, and sharing an ice cream soda. Often teenagers double-dated and took in a movie if they had the money. If they really had the money, they might get a hamburger after the show. Money or not, necking was not unknown to teenagers in those days.

Due to the Depression, children were forced to grow up fast back then. After her sophomore year in high school, Orvalette quit school and went to work. Just a month or so shy of being 17, she got married. A year later I was born.

Mother

(1922-2001)

Mother

Mother